Viewable PDF

Printable PDF

To Request a FREE hard copy of this booklet, please write to: contact@eternalgod.org

Introduction

This booklet addresses a topic that might seem ancient, irrelevant and too boring to consider in our busy 21st century lifestyle. Why should we care about what the ancient Israelites did in the wilderness thousands of years ago? Why should we take the time to read about their sacrifices and their tabernacle? Besides, didn’t Jesus’ death abolish these ancient rites, so that there could not possibly be any importance attached to them, at least for true Christians, right?

Well, you just might be surprised!

The fact of the matter is, the sacrifices and the tabernacle in the wilderness have a very DEEP meaning for true Christians today! God was very specific—for good reason—when He instructed Moses and ancient Israel on the sacrificial system and the tabernacle in the wilderness, and their relevance for us today is NOT to be cast aside!

Be prepared now, for an astonishing journey through the pages of history, as well as the prophecies that point to events that are yet to be fulfilled, and you will begin to see the bigger picture of how the sacrificial system and the tabernacle in the wilderness are very relevant in YOUR life today!

Chapter 1—What Is the Sacrificial Offering System?

The sacrificial system is described in detail in the book of Leviticus. The Hebrew title of the book is, “And He Called.” The Jewish Talmud calls it the “Law of the Priests” and the “Law of the Offerings.” In the Greek Septuagint, it is called, “That Which Pertains to the Levites,” from which the Latin name “Leviticus” is derived.

The theme of the book is the admonition for God’s people to become “holy” (Leviticus 19:2; 20:26). The people of ancient Israel did not become a holy people at that time, but God says that they will become a holy people in the future (Isaiah 62:12). True Christians today are already called a holy people, a “holy [or “royal,” compare 1 Peter 2:9] priesthood, to offer up spiritual sacrifices acceptable to God” (1 Peter 2:5).

Sacrifices—Past, Present and Future

The Bible reveals the correlation between the ancient sacrificial offering system described in the book of Leviticus and the way we worship today, as well as future worship in the Millennium.

Sacrifices Before Moses’ Time

The Bible reveals that offerings and sacrifices were already being given before the sacrificial system was established—long before the time of Moses.

Genesis 4:3–4 gives a report of offerings presented by Cain and Abel. They apparently knew of the custom of bringing various offerings from time to time; in this case, grain and burnt offerings. However, Cain apparently brought his sacrifice grudgingly, while Abel brought his offering willingly. We are told that God accepted the offering that Abel brought, but rejected Cain’s offering.

In Genesis 8:20, we have a report of Noah’s burnt offering, which was accepted by God. We also read that Job offered burnt offerings to God (Job 1:5), and that God commanded Job’s three friends to give a burnt offering (Job 42:8)

When dealing with the Old Testament sacrificial offering system under Moses, we must understand that it did not include wrong or unholy laws. The sacrificial system was enacted to deal with the sins of carnal people who had not received the Holy Spirit. God certainly would have preferred, of course, that people not sin at all (compare Jeremiah 7:21–23; Psalm 51:16–19). This still can be said of true Christians today. God wants us to not sin, so that we can then claim forgiveness through the sacrifice of Jesus Christ.

Sacrifices Under Christ and the Early New Testament Church

We find that the sacrificial offering system was administered during the time of Christ. Luke 2:22–24 tells us that Mary and Joseph gave burnt and sin offerings (compare Leviticus 12:1–8); and we read in Luke 5:12–14 that Jesus commanded a healed leper to give an offering. That particular offering included all types of sacrifices described within the sacrificial system; i.e., a grain offering, a sin offering, a burnt offering, a trespass offering and a subtype of the peace offering (compare Leviticus 14:10–13; all to be discussed below).

It is true, of course, that after the death of Christ, sacrifices were no longer necessary (compare Hebrews 10:1–10, specifically addressing burnt offerings). Hebrews 10:18 tells us that “there is no longer an offering for sin.” However, it was not prohibited to participate in the sacrificial offering system after Christ’s death. Jewish Christians sacrificed until the destruction of the temple in 70A.D.

We read in Acts 21:18–24 that Paul participated in the offering system. When following the “customs” of the Jews, he did the following: “Then Paul took the men, and the next day, having been purified with them, entered the temple to announce the expiration of the days of purification, at which time an offering should be made for each one of them” (verse 26).

It was of course not sinful for Paul to participate in these customs, although they were no longer required. Paul said that he became a Jew to the Jews in order to win some (1 Corinthians 9:20). And, although he had made it clear that circumcision was no longer required, he still circumcised Timothy, for the Jews’ sake, in order not to place a stumbling block before them (Acts 16:1–3). He did it not for the sake of the believing Jews—for he brought with them the decree of the apostles and elders to satisfy them that circumcision was no longer necessary—but rather for the sake of the unbelieving Jews who would not have allowed an uncircumcised person to teach in their synagogues.

Later, Paul wrote the letter to the Hebrews to show the Jewish Christians that they did not need a physical temple and that participation in the sacrificial offering system was no longer required.

It is important to understand that the sacrificial system was never enforced on Gentiles who became Christians (Acts 15:19–20). At the same time, they had to abstain from those things that had been part of a pagan offering system. As we explain in our booklet, “And Lawlessness Will Abound…”, on page 17, the four items to be avoided (idols, sexual immorality, strangled meat and blood) were all prohibitions listed in the context of the sacrificial system within the Law of Moses. So as to avoid any misunderstanding, the apostles and elders clarified to the Gentiles that these laws were still valid and binding on them.

Adam Clarke’s Commentary on the Bible explains it in this way:

“By the first, Pollutions of Idols, or, as it is in Acts 15:29, meats offered to idols, not only all idolatry was forbidden, but eating things offered in sacrifice to idols, knowing that they were thus offered, and joining with idolaters in their sacred feasts, which were always an incentive either to idolatry itself, or to the impure acts generally attendant on such festivals.

“By the second, Fornication, all uncleanness of every kind was prohibited; for [“porneia”] not only means fornication, but adultery, incestuous mixtures, and especially the prostitution which was so common at the idol temples, viz. in Cyprus, at the worship of Venus; and the shocking disorders exhibited in the Bacchanalia, Lupercalia, and several others.

“By the third, Things Strangled, we are to understand the flesh of those animals which were strangled for the purpose of keeping the blood in the body, as such animals were esteemed a greater delicacy.

“By the fourth, Blood, we are to understand, not only the thing itself… but also all cruelty, manslaughter, murder, etc., as some of the ancient fathers have understood it.”

As mentioned, even though the sacrificial system was not to be enforced on the Gentiles, Acts 15:19–20 shows that Gentiles were not prohibited from participating in it; but when they did, they had to do so in accordance with God’s instructions.

Sacrifices Before Christ’s Return and in the Millennium

God reveals to us that offerings will be given during the Millennium.

For instance, we read about the time of the Millennium in Ezekiel 43:18, 22, 27: “And He said to me, ‘Son of man, thus says the Lord God: “These are the ordinances for the altar on the day when it is made, for sacrificing burnt offerings on it… On the second day you shall offer a kid of the goats without blemish for a sin offering… When these days are over it shall be, on the eighth day and thereafter, that the priest shall offer your burnt offerings and your peace offerings on the altar…”’”

Another passage that describes the time of the Millennium is Ezekiel 44:15, 29–30. It refers to the offering of fat and blood, as well as grain offerings, sin offerings and trespass offerings. Describing the same time setting, Zechariah 14:21 says that “Everyone who sacrifices shall come” to the LORD’S house—a new Temple in Jerusalem.

From these Scriptures, we see clearly that burnt offerings, peace offerings, grain offerings, sin offerings and trespass offerings will be given in the Millennium.

We also understand that the Jews will give offerings again, for a while, just prior to the return of Jesus Christ. In Malachi 3:2–4, these offerings, which apparently may not be pleasing to God, are compared with the offerings that will be given in the Millennium, which WILL be pleasing to God.

Yes, in the future, sacrifices will be reinstated—at least on a temporary basis—but GOD will NOT reinstate the Old Testament sacrificial SYSTEM. That is, the sacrifices that will be given before Christ’s return (Daniel 12:11), and those given in the Millennium (compare Ezekiel 40:38–43, which describes the preparation of burnt offerings, sin offerings and trespass offerings during the Millennium), are not the same as those that were part of the old covenants with the nations of Israel and Judah. The New Testament tells us that the sacrifices—as part of the Old Testament system—are no longer valid. The Levites will still officiate over sacrifices, but these sacrifices will not be given pursuant to the same system that existed in the Old Testament, under Moses.

The Bible also indicates that, at the beginning of the Millennium, new moons will be kept in conjunction with the bringing of sacrifices (Ezekiel 45:17, 46:1, 3, 6; Isaiah 66:20–23). However, there is no Biblical injunction for us today that would compel us to either celebrate new moons or bring sacrifices.

It is important to understand that the millennial sacrifices will NOT be brought for the purpose of forgiveness of sin! Only Christ’s shed blood accomplished this—once and for all! But God introduced the sacrificial system to ancient Israel because Israel had sinned and the sacrifices served as a reminder of their sins. Apparently, for the same reason in the Millennium, sacrifices will be brought so that carnal, unconverted people can begin to appreciate the awesome purpose and meaning of Christ’s Sacrifice and how God looks at sin.

Animal sacrifices, especially, illustrate what sin does to us and others, as well as what Christ did for us. They teach us one reason for the suffering of innocent and righteous people: Even Jesus Christ suffered, although He was totally innocent. The killing of innocent animals points at the suffering and ultimate death of Jesus Christ.

Of necessity, there will be an ongoing physical priesthood serving throughout the Millennium in order to properly administer the sacrifices. The physical sacrifices extant at that time will be brought in Jerusalem—in a newly-built temple—and will be part of the new administration that God’s Kingdom will usher in.

What We Can Learn from the Sacrifices

We DO know that all five types of the Old Testament sacrifices will be given again in the future, after Christ has returned, and we DO understand that they hold a deep symbolic meaning. The ancient sacrifices pointed to Christ and what He would accomplish by sacrificing His own life. In this way, the sacrifices foreshadowed the substance, or essence, of the ultimate reality—Christ—the Savior. Most people in Old Testament times did not understand that, nor do many today understand this very important symbolism.

The sacrifices show us how careful and diligent the people had to be in following God’s detailed and specific instructions—to the letter—and even though most people did not understand the real meaning behind those instructions, they were still obligated to follow them, precisely.

The same can be said for our worship of God today. We may not know why God instructs us to do a certain thing or to avoid doing something. We may, in fact, think we know better. God’s command in a given situation may not sound “logical,” reasonable or convincing to us. But God does know what is best for us, and He requires that we follow Him—obeying Him exactly in every detail—whether we understand the reason for it or not.

Five Types of Offerings and What They Symbolize

There are only five types of offerings that God required: the burnt offering, the grain offering, the peace offering, the sin offering and the trespass offering. As we will show, they portray five steps in our reconciliation with God—actually picturing what Christ did for us and how we are to respond to Him.

Five Steps of Reconciliation

These five types of offerings are given here in brief summary form as they correlate to the five steps of reconciliation with God. We will discuss them in much more detail in the ensuing sections of this booklet.

The burnt offering foreshadows the first step toward our renewed contact or reconciliation with God—loving God. We are to strive to live sinless lives and to become living sacrifices, thus expressing our love toward God.

The grain offering foreshadows the second step of our reconciliation with God—loving our neighbor. We are to strive to live a sinless life toward our neighbor, thus expressing our love for our neighbor.

The peace offering foreshadows the third step of our reconciliation with God, and is what the name implies—peace. We express peace by having continual peaceful fellowship with God and with our neighbor.

The sin offering foreshadows the fourth step of our reconciliation with God—forgiveness of our sins. We can receive continual forgiveness of sin and our sinful nature through the sacrifice of Jesus Christ.

The trespass offering foreshadows the fifth step of our reconciliation with God—forgiveness of our sins and trespasses against our neighbor. Additionally, this offering requires some form of restitution in order to fully reconcile with our neighbor.

Our complete reconciliation with God is made possible through Christ’s Sacrifice for our sins and trespasses and our sinful nature, along with having Him continually living His life in us, thereby continually purifying us. But we have to do our part as well. We have to accept what Christ did for us in the past and what He is doing for us today, and we have to be willing participants in the process of becoming perfected.

The ancient sacrifices foreshadowed what Christ would do for us, and even though they are not required to be performed today, the significance of the symbolism contained in each type of sacrifice cannot be ignored by true Christians today. They show us—in symbolic and figurative ways—how we are to approach and respond to our God and our Savior—in appreciation and obedience—by living a sinless life, thus becoming a living sacrifice.

The Five Types of Offerings in Detail

The Burnt Offering

The burnt offering is described in Leviticus 1:1–17. For space limitations, we will not quote the entire passage, but we strongly recommend that you study this passage in your Bible before continuing to read this booklet. In doing so, you will gain a better understanding as we explain the details of the offering.

Purpose of the Burnt Offering

To bring about our reconciliation with God, by loving God; it foreshadowed the first step toward renewed contact with God.

The Kind of Sacrifice Offered

A male animal without blemish; i.e., a bull, a lamb, a goat or a dove.

What Was Offered?

The entire animal was burned.

Consumption

No one, not even the priests, ate anything from that animal.

Symbolism

It symbolized Christ.

The innocent, sinless Jesus Christ gave Himself as a sacrifice. Leviticus 1:2 shows that the burnt offering was a voluntary offering—as Christ gave His life for us voluntarily (John 10:17–18).

The animal sacrifice had to be without blemish (Leviticus 1:3)—as Christ was without blemish—without sin (compare 1 Peter 2:21–22).

The animal was a sweet-smelling aroma (Leviticus 1:9)—as it pleased God to give His only-begotten Son to die for us so that man could enter the Family of God and become an immortal Spirit being, AND it pleases God when He sees us respond to Christ’s Sacrifice.

All the animals that could be sacrificed symbolized Christ.

They included a bull (verses 3, 5), symbolizing strength (In Isaiah 34:6–7, the destruction of powerful Edom is pictured as a slaughter of wild oxen, young bulls and mighty bulls).

They also included a lamb or a goat (verse 10), which portrays acceptance of God’s Will without complaining (Isaiah 53:7), as well as persistence and strong leadership.

Another animal that could be sacrificed was a dove (verse 14), portraying innocence and sincerity (Matthew 10:16).

In addition, the burnt offering symbolized the true Christian, in whom Jesus Christ lives.

We are called living and holy sacrifices (Romans 12:1). We have to give our life as a living sacrifice to God. As the burnt offering was completely burned (Leviticus 1:9), so we must give ourselves completely and without reservation to God. As members of God’s Church, we have to become without blemish (Ephesians 5:25–27).

Gentiles to be a Sacrifice

In this context, let us also consider the following remarkable statement found in Romans 15:15–16, showing that converted Gentiles are also to be living sacrifices. The Authorized Version reads: “That I should be the minister of Jesus Christ to the Gentiles, ministering the gospel of God, that the offering up of the Gentiles might be acceptable, being sanctified by the Holy [Spirit].”

Other translations render this passage as follows:

“…so that the Gentiles might become an offering acceptable to God” (New International Version); “…so that gentiles might become an acceptable offering” (New Jerusalem Bible); “…to offer the Gentiles to him as an acceptable sacrifice” (Revised English Bible); “…so that the Gentiles, when offered before him, may be an acceptable sacrifice” (Century Translations in Modern English).

Further Symbolism of the Burnt Offering

Before the burnt offering was sacrificed, it was cut into its pieces (Leviticus 1:6)—the head, the fat (verse 8), as well as its entrails and the legs, which also had to be washed (verse 9). They all were to be burned as well. But why did God insist on prior special “treatment” and emphasis? The reason is that the different “parts” represented something.

The head represents our thoughts and intellect (Isaiah 1:5–6 says that the whole head of Israel is sick).

The fat represents a blessed human being (Deuteronomy 31:20).

The entrails (The Authorized Version states: “inwards”) represent our feelings and motivation. Psalm 64:6 tells us that both the inward thought and the heart of man are deep. Jeremiah 31:33 says that God will put His law in the inward parts of the people (compare the Authorized Version).

The legs represent our walk—our way of living. In the Hebrew, as in the English, the words “legs” are used in the plural—referring to all of them—showing unity and coordination; one leg does not move to the left, while another leg moves to the right. The legs represent coordinated strength in our way of living. Compare Ephesians 4:1 (“walk worthy”); Ephesians 5:15 (“walk circumspectly as wise, not fools”); 1 Kings 18:21 (“how long do you limp on both sides?”, Luther Bible); Hebrews 12:12–13 (“make straight paths for your feet so that what is lame may… be healed”).

The legs had to be washed. The washing of our feelings and our walk represents our cleansing (compare Ephesians 5:25–26).

The person giving the offering had to lay his hand on the head of the animal (Leviticus 1:4), indicating his identification with the sacrifice. He had to kill it himself (verse 5), as he was responsible for and guilty of the death of Jesus Christ—as all of us are, individually and collectively. Isaiah 53:5 says that Christ was wounded—pierced through—for our transgressions, and Isaiah 53:8 says that He was stricken for the transgression of God’s people.

Meaning for Us Today

The sacrifice was burnt—as a complete and total burnt offering. Mark 9:49 says: “For everyone will be seasoned with fire, and every sacrifice will be seasoned with salt.”

We have to lead a sinless life, a life which is tested and found genuine through fire (compare 1 Peter 1:6–7; 4:12). Every part of a Christian—his thoughts, feelings and his deeds—must be subjected to God, as Christ was submissive to the Father. And, we must love God totally—before anything or anyone else (compare Matthew 22:37).

The burnt offering was a request to God to accept the fruit of the Holy Spirit, which is being produced in the life of a true Christian. We read in Romans 15:16 that the offering or sacrifice of the Gentile Christians is acceptable when sanctified through the Holy Spirit. We also read in 1 Peter 2:4–5, that we are to offer up spiritual sacrifices acceptable to God through Jesus Christ. When Christ lives in us through the Holy Spirit, and when we follow His lead, then we are totally accepted by God, and even our death will be precious in His sight (Psalm 116:15; Isaiah 57:1–2).

To reiterate, the burnt offering symbolizes our love toward God. Our love toward God is summarized in the first four of God’s Ten Commandments.

The Grain Offering

The grain offering is described in Leviticus 2:1–16. Again, for reasons of limited space, we are not quoting the entire passage here; but please read the passage in your Bible before continuing, so that you can fully appreciate the connection between the past, the present and the future sacrifices.

The grain offering was sometimes given together with a drink offering (Leviticus 23:13). They constituted non-animal offerings, but they were sometimes given together with animal sacrifices (compare Numbers 15:2–12).

Purpose of the Grain Offering

It foreshadowed the second step toward our reconciliation with God, by loving our neighbor.

The Kind of Sacrifice Offered

Fine flour, oil, frankincense; unleavened cakes with oil; and salt.

What Was Offered?

Handful of fine flour with oil and frankincense (Leviticus 2:2).

Consumption

The priests ate the sacrifice.

Symbolism

It symbolized Christ.

Christ gives Himself as the true bread for man (compare John 6:48–51). Christ made clear that He is the Bread of Life.

The grain offering symbolizes Christ’s love towards us—His neighbors. This Godly love toward neighbor is summarized in the last six of the Ten Commandments. [As we mentioned, the first four commandments summarize our love toward God—symbolized in the burnt offering.] Therefore, the burnt offering and the grain offering are closely connected (Numbers 28:11–12; Judges 13:19; Ezra 7:17).

The Grain Offering symbolized also the individual Christian.

We have to symbolically “eat” Christ—the Bread of Life (compare John 6:48, 50). We have to live by every word of God that comes out of the mouth of God (Matthew 4:4).

We are reconciled to God—on a continual basis—if we love God AND our neighbor. 1 John 5:2 says that we know that we love the children of God when we love God and keep His commandments.

1 John 4:12 adds that if we love one another, God abides in us; and 1 John 4:20 says that if anyone says, I love God, and hates his brother, he is a liar; for he who does not love his brother, cannot love God, either.

As Christians, we are to love our neighbor (Matthew 22:39; Romans 13:9–10).

The grain offering is a sweet aroma to the Lord (Leviticus 2:2), as it is pleasing to God when we love our neighbor. Compare Ephesians 5:1–2: “Therefore be imitators of God as dear children. And walk in love, as Christ also has loved us and given Himself for us, an offering and a sacrifice to God for a sweet-smelling aroma.”

Let us also take note of the symbolism of the different ingredients of the grain offerings.

The grain offering had to be mixed with oil (Leviticus 2:2–5), symbolizing the anointing with the Holy Spirit (compare Acts 10:38; Isaiah 61:1). We can only truly love our neighbor with Godly love, when, and as long as God’s Holy Spirit lives in us. Romans 5:5 tells us that the love of God has been poured out in our hearts by the Holy Spirit that God gave us.

The grain offering included frankincense (Leviticus 2:2)—but not honey (verse 11), as honey is perishable. Sweet incense or frankincense is symbolic for the prayers of the saints (compare Psalm 141:2; Revelation 5:8). Revelation 8:3 tells us that our prayers are offered with much incense upon the golden altar in front of the throne of God in heaven. In the context of the grain offering (picturing love toward neighbor), we see that our prayers need to express our love toward our neighbor.

We read that the Magi gave frankincense as a gift to the Christ Child (Matthew 2:11). This has been understood as a reference to Christ becoming our High Priest, who represents us before God the Father in heaven.

The grain offering included salt (Leviticus 2:13), indicating permanency and incorruption (compare Numbers 18:19). Our love toward our neighbor must be enduring and lasting.

Wine was another ingredient of the grain offering (compare Numbers 15:5 for the drink offering—a subtype of the grain offering). Wine represents the blood of Jesus Christ. As true Christians, we are instructed to partake of the Passover, once a year, by eating bread and drinking wine (compare John 6:53–54).

Normally no leaven was to be offered with the grain offering (Leviticus 2:4, 5, 11), as leaven is sometimes used in the Bible to symbolize sin (compare 1 Corinthians 5:7). Leaven was permitted to be offered in the context of the offering of the firstfruits—but not on the altar—to show that Christians, who are called “firstfruits” (James 1:18; Revelation 14:4) are not yet without sin. When leaven was offered, it was NOT a sweet-smelling aroma (Leviticus 2:12).

The Peace Offering

The Peace Offering is described in Leviticus 3:1–17; 7:11–18, 28–34. We again urge you to read these passages in your Bible before continuing, to gain the full benefit of what you are reading in this booklet.

The peace offering was divided into five different categories of offerings:

- the Sacrifice of Thanksgiving (Leviticus 7:12–15)

- the Sacrifice for a Vow (Leviticus 7:16–17)

- the Sacrifice as a Voluntary or Freewill Offering (Leviticus 7:16–18)

- the Sacrifice as a Heave Offering for the priest (Leviticus 7:14, 28–34)

- the Sacrifice as a Wave Offering for the priest (Leviticus 7:28–34)

Purpose of the Peace Offering

It foreshadowed the third step toward our reconciliation with God, by having peaceful fellowship with God, as well as a peaceful meal with the priest and the one who brings the offering (“the offeror”).

A good relationship between the true ministry of God and the membership is important. This includes respect for the office of the ministry. The peace offering pictures the priest representing the entire community or “church,” when he [representing all the people] ate with the offeror.

We find a similar analogy in Matthew 18:17. In that passage, the word “church” refers to the ministry. After an unrepentant sinner refuses to listen to the offended brother or sister, as well as selected witnesses, it is the “church’s” responsibility—that is, the responsibility of the ministry, representing the church—to speak to the sinner, in a last ditch effort to show him or her the severity of his or her actions.

The Kind of Sacrifice Offered

Blameless male or female ox (Leviticus 3:1), lamb or goat (vv. 7, 12).

What Was Offered?

Only the fat which covers the entrails, the kidneys and the fatty lobe attached to the liver had to be burned to the LORD.

Consumption

The consumption of the unburned parts depended on the type of the offering:

The high priest received the breast during a wave offering (compare Leviticus 7:30).

The priests received the right thigh during a heave offering (compare Leviticus 7:33–34).

The rest was eaten by the offeror—the one who offered the animal. The peace offering constituted the ONLY OFFERING in which the offeror shared, by eating a portion of the sacrifice.

If the peace offering was a thanksgiving offering, it had to be eaten on the same day.

If the peace offering was a voluntary or free will offering, or a vow offering, it had to be eaten on the first or the second day.

Symbolism

Since God and the priest and the offeror participated in the consumption of the sacrifice, it symbolized our fellowship with God and our brethren (compare 1 John 1:3).

It was a sweet-smelling aroma (Leviticus 3:5), just as our true fellowship with God and our fellow brethren is pleasing to God. It is also very pleasing to God that we have become a part of His very Family—the Family of God. We read in 1 John 3:2 that we are already the children of God.

The peace offering symbolizes peace between God and man. In Isaiah 9:6–7; 53:5, we find the symbolism referring to Jesus Christ—our “Peace”—who will bring us peace; and in Psalm 133:1, we find the symbolism referring to Christians who live in peace with their brethren.

As mentioned, a thanksgiving offering had to be eaten on the same day—showing that we must not delay to give thanks to God for what He does for us (compare Hebrews 13:15–16).

A vow offering had to be eaten on the first or on the second day. This indicates that we should make careful consideration before we make a vow or a promise. Once we make it, we must keep it (compare Ecclesiastes 5:1–7).

The Sin Offering

The sin offering is described in Leviticus 4:1–35; 5:1–13. When reading these passages in your Bible, please note that the headline of Leviticus 5:1 is confusing in the New King James Bible, as it gives the impression that the trespass offering begins with Leviticus 5:1. This is false. The trespass offering does not start until Leviticus 5:14, compare the Luther Bible. Please note, too, that Leviticus 5:6 is poorly translated in the New King James Bible. Rather than saying, “he shall bring his trespass offering to the LORD,” it should read, “guilt offering.” Leviticus 5:6 is still talking about the “sin offering.”

Since the sin offering deals with sin, let us briefly mention what sin is. Basically, we find three Biblical definitions of sin:

1 John 3:4 tells us that “sin is lawlessness” or—as the Authorized Version has it—“the transgression of the law.”

Romans 14:23 tells us that “whatever is not from faith is sin.”

And James 4:17 tells us: “…to him who knows to do good and does not do it, to him it is sin.”

The sin offering includes, symbolically, all these aspects of sin.

Purpose of the Sin Offering

It constituted a sacrifice for a specific sin for which no restitution was possible. It foreshadowed the fourth step toward our permanent reconciliation with God, showing the importance of maintaining a peaceful relationship with God.

No restitution was possible in those kinds of sacrifices, symbolizing the fact that nothing we can do entitles us to the Sacrifice of Jesus Christ. We cannot earn our salvation. No restitution or payment, and no amount or degree of penance will make us clean in the sight of God (compare Proverbs 20:9).

The Kind of Sacrifice Offered

A young bull without blemish if a priest sins (Leviticus 4:3); a young bull if the congregation sins (Leviticus 4:14); a male kid of the goats without blemish if a ruler sins (verse 23); or a female kid of the goats or a female lamb without blemish if a common person sins (verses 27–28, 32).

If the common person cannot offer a kid of the goats or a lamb as a sacrifice, he is permitted to bring two turtledoves or two young pigeons (Leviticus 5:7). If he can’t even do that, he can bring a certain amount of flour (Leviticus 5:11).

These provisions ensured that EVERYBODY who has sinned was able to bring the sin offering.

Note Hebrews 9:22 in this context, which says that “ALMOST” all things are by the law purged or purified with blood. As was the case in Leviticus 5:11, in rare circumstances, atonement could be received without the shedding of blood (compare also Numbers 16:46; 31:50).

We might also note that the burnt and the grain offerings were sometimes given together with the sin offering (compare Numbers 28:11–15)—picturing the fact that sin is still in our lives, even after conversion, requiring the “revisiting” of the previous steps of establishing a permanent relationship and reconciliation with God.

What Was Offered?

The fat was burned on the altar; or in the case of flour, a handful was burned.

Consumption

Priests ate the sacrifice (including the flour as a grain offering, Leviticus 5:13); the one who gave the offering did not eat from it (Leviticus 6:25–26).

This shows the part that a priest or a minister has in the pronouncement of the forgiveness of sin. Only God forgives sin, but He uses His priests, prophets and ministers, at times, to make the fact clear to others that God forgave sins (compare 2 Samuel 12:13; John 20:22–23).

Symbolism

The sin offering symbolizes Christ who carries our sins. The animal [carcass] was burned outside the camp (compare Leviticus 4:11–12, 21). Christ was killed outside the City of Jerusalem (compare Hebrews 13:12–13). Sin will not enter the New Jerusalem (Revelation 21:27; 22:14–15).

The sin offering also symbolized the individual Christian. Christ died for our sins (compare 2 Corinthians 5:21), including our sinful nature (compare Romans 8:3–4; 7:18). We need to crucify our individual sins, as well as our human carnal nature (compare Galatians 5:16, 24). We must become dead to sin—not just individual sinful acts (compare Romans 6:10–11). We must die to sin and be cleansed from sin on a continual basis (compare 1 John 1:7–9).

The Trespass Offering

The trespass offering is described in Leviticus 5:14–19; 6:1–7; 7:1–17. Again, please carefully read these passages from your Bible before continuing.

Purpose of the Trespass Offering

It constituted a sacrifice for sin for which restitution WAS possible. It foreshadowed the fifth and final step toward our permanent reconciliation with God, showing the importance of maintaining a peaceful relationship with our neighbor.

The Kind of Sacrifice Offered

A ram without blemish (Leviticus 5:15).

What was Offered?

Only the fat, which was burned (Leviticus 7:3–5).

Consumption

The priest ate the sacrifice (Leviticus 7:7). The one who brought the sacrifice did not eat from it.

Again, this shows the role of the priest or minister in the pronouncement of forgiveness of sin, as well as regarding physical healing (compare James 5:14–16).

Symbolism

The sin offering is closely related to the trespass offering (compare Leviticus 7:7). The sin offering symbolized Jesus Christ’s ultimate Sacrifice. We read that Christ died for our sins and trespasses (2 Corinthians 5:19; Ephesians 2:1–5; Colossians 2:13). While sin many times describes an unlawful action against God, trespasses relate to unlawful conduct against our neighbor.

The trespass offering was made for individual sinful acts—not for the sinful nature per se. It was also necessary to eradicate or recompense for the consequences of trespasses (Leviticus 5:16). We should note, however, that even though restitution was made toward the wronged neighbor, God still required, in addition to that, the bringing of an offering—because when we trespass against our neighbor, we at the same time sin against God.

The trespass offering symbolized also the individual Christian. Christ’s Sacrifice is sufficient to forgive us our sins, our sinful nature and even the damage that we might have caused to others by our conduct (compare Hebrews 10:14). But we are still to go to our neighbor to bring about reconciliation with him, whether he has sinned against us or we have sinned against him, or even if we know that he thinks we did. Matthew 18:15 emphasizes the case when our brother sins against us, while Matthew 5:23–26 describes our responsibilities toward our brother when our brother has something against us; that is, when we have wronged him.

All Sacrifices Listed

A summary listing of these five sacrifices is also given in Leviticus 7:37–38 as follows: “This is the law of the burnt offering, the grain offering, the sin offering, the trespass offering, the consecrations [for the priests, as described in Leviticus 8:1 ff] and the sacrifice of the peace offering, which the Lord commanded Moses on Mount Sinai, on the day when He commanded the children of Israel to offer their offerings to the Lord in the wilderness of Sinai.”

It is interesting to note that God changes the order slightly in this summary, placing the sin and the trespass offering BEFORE the peace offering. He did not focus here on the necessary order of steps to establish permanent reconciliation with God, but He wanted to emphasize the ultimate goal of our Christian life—to obtain and maintain PEACE with God and our neighbor. We can only accomplish this when the peace of God lives in us.

The Five Steps of Reconciliation with God

In a brief recap of the five types of offerings, we can see how they correlate with the five steps toward our reconciliation with God. As previously mentioned, all Old Testament sacrifices point toward Christ. They picture what Christ did for us, what He is still doing for us today, and how we are to respond to Him. They picture reconciliation with God.

The Burnt Offering = The First Step toward our reconciliation or renewed contact with God.

Admonition: Strive to live a sinless life toward God; become a living sacrifice, out of love toward God

The Grain Offering = The Second Step toward our reconciliation with God.

Admonition: Strive to live a sinless life toward our neighbor, out of love toward our neighbor.

The Peace Offering = The Third Step toward our reconciliation with God.

Admonition: Have continued peaceful fellowship with God and our neighbor.

The Sin Offering = The Fourth Step toward our reconciliation with God.

Admonition: Obtain continued forgiveness of our sins against God and our sinful nature, through Jesus Christ.

The Trespass Offering = The Fifth Step toward our reconciliation with God.

Admonition: Obtain continued forgiveness of our individual sins and trespasses against our neighbor, through Christ, requiring restitution (by going to our neighbor).

Summary of the Symbolism of the Sacrificial System

Our permanent and enduring reconciliation with God is made possible only through Christ’s Sacrifice for our sins against God and neighbor, and our sinful nature, as well as His living in us and continually purifying us. But we have to do our part. We have to accept what Christ did for us in the past, and what He is doing for us now, and we have to be willing participants in the process of becoming more and more perfect.

The sacrifices foreshadowed what Christ would do for us. Even though they are no longer required to be given by us today, they have great symbolic meaning for us. They show, in figurative ways, how we are to respond to our great Savior, King and Lord. We are to appreciate and obey God’s Word; we are to be living sacrifices; and we are to become more and more perfect in developing the very character and mind of God.

Chapter 2—The Tabernacle in the Wilderness

As we saw in the first chapter, God was very specific in His instructions to the Israelites regarding the various types of sacrifices. We will see in this chapter that He was also very specific about where those sacrifices were to be brought. God did not want the Israelites to sacrifice just anywhere. Rather, they had to bring their offerings to a place that was designed specifically for that purpose—the tabernacle in the wilderness. And, like the sacrifices performed in it, the tabernacle in the wilderness also carries a very deep meaning for us today.

Those who like to be entertained by movies, have undoubtedly seen Steven Spielberg’s “Raiders of the Lost Ark.” If you have seen it, you may recall the climactic scene when the ark of the covenant was opened and evil persons were exterminated by some ghostly apparitions ascending from the ark. That, of course, was pure Hollywood fiction!

But what about the true ark of the covenant? What happened to it? Originally, it was placed in a big tent, referred to in Scripture as the Tabernacle. But the ark has been lost from sight. As is the case with Noah’s ark, there is wild speculation as to where it may be, and whether or not it is going to be found and excavated before, or after, Christ’s return. Some even claim that the ark of the covenant will be found before Christ’s return so as to motivate the Jews to begin again to bring sacrifices. That, of course, is pure speculation and is not backed by any Biblical evidence whatsoever.

What then, became of the ark of the covenant?

According to Jewish tradition (compare 2 Maccabees 2:1–8, Revised Standard Version), Jeremiah hid the ark, the tent and the altar of incense in a cave on the mountain where Moses was buried, and he then sealed the entrance. He told the people: “The place shall remain unknown until God gathers his people together again and shows his mercy. Then the Lord will disclose these things, and the glory of the Lord and the cloud will appear…” (verses 7–8).

But this “tradition” does not seem to square with Scripture. We read in Jeremiah 3:16 regarding the ark of the covenant at the time when God will gather His people: “’Then it shall come to pass, when you are multiplied and increased in the land in those days,’ says the LORD, ‘that they will say no more, ‘The ark of the covenant of the LORD.’ It shall not come to mind, nor shall they remember it, nor shall they visit it, nor shall it be made anymore.’”

Earthly Tabernacle

We read in Exodus 25:8–9 that the entire earthly tabernacle and its furnishings were to be made according to a pattern shown by God to Moses. The earthly tabernacle was to reflect and resemble a heavenly reality—a heavenly tabernacle (compare Acts 7:44–47; Hebrews 8:4–5; 9:1, 11, 23–24; Revelation 11:19; 15:5).

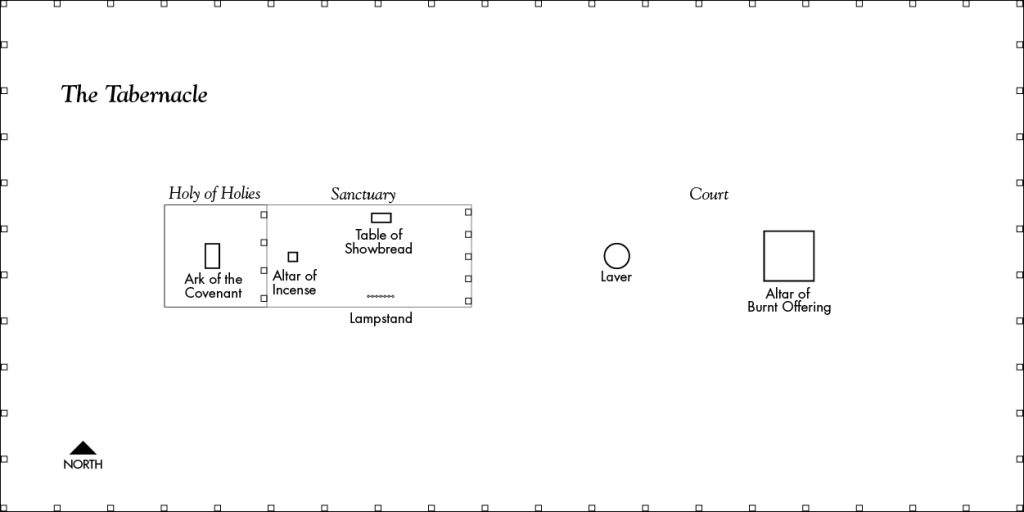

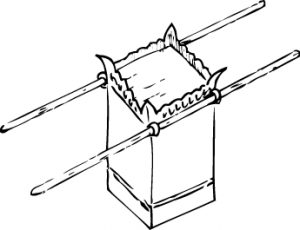

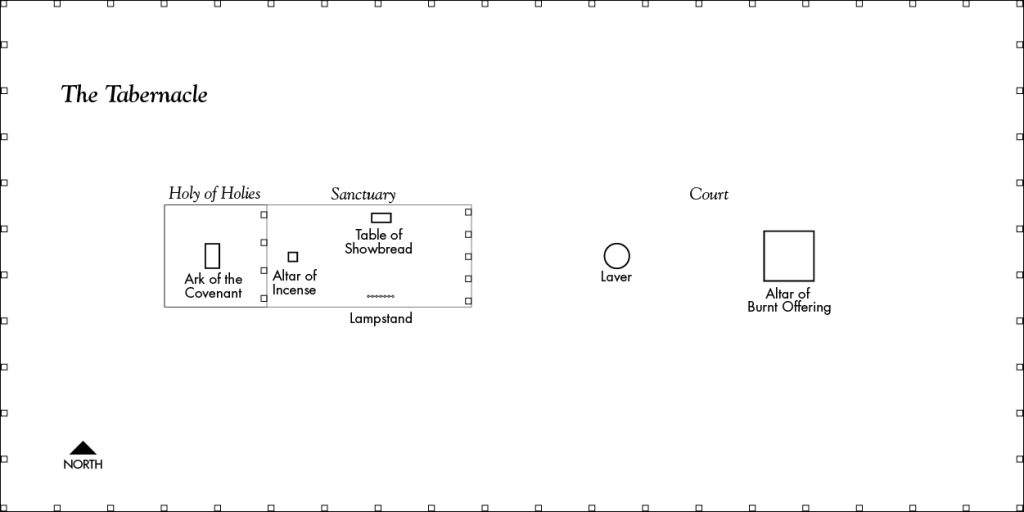

In the New Testament, Paul gives us the following summary of the tabernacle in the wilderness and its furnishings. We read in Hebrews 9:2–5: “For a tabernacle was prepared: the first part, in which was the lampstand, the table, and the showbread, which is called the sanctuary [holy place; literally, “holies”]; and behind the second veil, the part of the tabernacle which is called the Holiest of All, which had the golden censer and the ark of the covenant overlaid on all sides with gold, in which were the golden pot that had the manna, Aaron’s rod that budded, and the tablets of the covenant [the Ten Commandments]; and above it were the cherubim of glory overshadowing the mercy seat…”

The entire complex of the tabernacle in the wilderness consisted of the court, which was surrounded by a fence or an entrance curtain, and the tent.

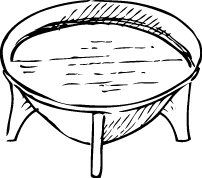

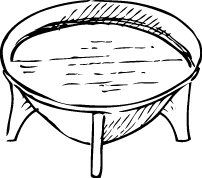

The Israelite would enter the court after passing the fence. Before him, and between him and the tent, was the altar of burnt offering. Behind the altar, but before the tent, was the bronze laver or bronze basin, for the use of the priests who would carry out the sacrifice on the altar of burnt offering. It was a large ceremonial vessel for washing—restricted to only the priests. The Latin word lavatorium and our word “lavatory” are derived from the word, laver.

The priest would go into the tent through a veil. The tent itself was divided into the Holy Place, or Sanctuary, and the Holiest of All, which was also called the Holy of Holies.

The Sanctuary or Holy Place contained:

The table of showbread, which stood at the right-hand or north side.

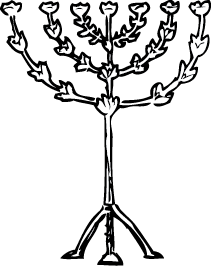

The lampstand with seven arms, which stood to the left or south side.

The altar of incense [which was placed before the second veil, which separated the Holy Place or Sanctuary from the Holy of Holies].

The Holy of Holies, also known as the Most Holy Place, contained:

The ark with the mercy seat and the two cherubim (angelic beings).

Later were added a golden pot with manna, Aaron’s rod that budded (compare Numbers 17:1–5), and, temporarily, the golden censor. In addition, the tablets of the covenant; that is, the Ten Commandments, were placed inside the chest or the ark of the covenant.

The tabernacle was set up one year after Israel’s exodus from Egypt (Exodus 12:2), and nine months after Israel’s arrival at Mount Sinai (Exodus 19:1).

Specific Measurements Given

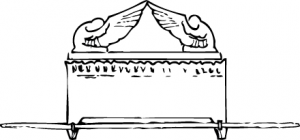

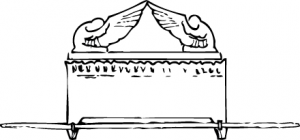

We read in Exodus 25:10 that the ark of the covenant was two and a half cubits in length, a cubit and a half was to be its width, and a cubit and a half its height.

A cubit was the length of a man’s arm from his elbow to his extended middle finger. The commonly accepted estimate for the cubit is 18 inches. The ark, then, would have been approximately 4 feet long and about 2-1/4 feet wide and high (exactly 3’9” x 2’3” x 2’3”).

The tabernacle tent took up 1/15th of the entire complex. The Holy Place measured 20 x 10 cubits; the Holy of Holies measured 5 x 5 cubits. The court measured 100 x 50 cubits (Ex. 27:18); or 150 feet x 75 feet, and was screened with linen curtains 7 ½ feet high.

In giving measurements in meters, the court, which was surrounded by a fence, would have been 50 x 25 meters.

The Tabernacle and the Temples

Once the tabernacle was finished, God filled it with His glory, as He also did when the temple of Solomon was built 500 years later, replacing the tabernacle. The ark of the covenant and some of the furnishings were placed in the temple (compare 1 Kings 8:4, 6–9). 1 Chronicles 9:23 refers to the temple as the “house of the tabernacle.” It also speaks of the temple as the house of the LORD, after the ark came to rest (compare 1 Chronicles 6:31). The temple was not just the successor to the tabernacle. The tabernacle, at least through its most important piece—the ark of the covenant—along with some other furniture, was actually located INSIDE the temple.

When Israel turned away from God, His glory and presence departed, and the temple was destroyed in 587 B.C. At that time, the tabernacle and its contents disappeared from the Bible. The temple was rebuilt—but the tabernacle was no longer in it—even though some items may have been.

For example, one of the candlesticks, which were later placed in Solomon’s temple, was taken and afterwards returned by the Babylonians. The candlestick in Herod’s temple might have been that candlestick that originated with the tabernacle in the wilderness. It was taken to Rome in 70 A.D., and nothing further is known about it.

Solomon’s Temple

When Solomon built a temple, following the instructions and the design of his father David, it was to represent a more permanent dwelling place for God—even though God does not dwell in temples made by human hands (compare Acts 7:47–50)—while the tabernacle was to represent a portable “temple.” God did not really dwell in either; it was merely a symbolic way of showing the “presence” of God. In that way, God will again “dwell” or “tabernacle” with man in the future (compare Leviticus 26:11; Revelation 21:3).

Solomon’s temple was patterned after the tabernacle in the wilderness. However, there were some distinctions: The tabernacle was exactly half the size of Solomon’s temple. The temple had a porch or “vestibule,” which the tabernacle did not have. Later, the temple built under Zerubbabel was patterned after Solomon’s temple. It had a porch as well, but it was only half that high. Under Herod, that temple was greatly remodeled, and the porch’s height was increased.

Details of Solomon’s Temple

The temple’s Most Holy Place or “inner sanctuary” (1 Kings 6:19; 8:6), which corresponded to the Most Holy Place of the tabernacle, was called also the “inner house” or “inner room” (1 Kings 6:27). The floors were made with the cedars of Lebanon (1 Kings 5:6; 6:16), and its walls and floor were overlaid with pure gold (1 Kings 6:20, 21, 30).

It contained two cherubim (1 Kings 6:23), corresponding to the two cherubim on top of the ark of the covenant of the tabernacle. Each had outspread wings, so that, since they stood side by side, the wings touched the wall on either side and met in the center of the room (1 Kings 6:24–28).

There were doors between it and the Holy Place, overlaid with gold (2 Chronicles 4:22); also a veil of blue, purple, crimson and fine linen (2 Chronicles 3:14), corresponding to the veil of the tabernacle, separating the Holy Place and the Most Holy Place. The Most Holy Place had no windows (1 Kings 8:12). It was considered the dwelling place of God, who must give us His light to see in darkness. In the Most Holy Place was placed the ark of the covenant.

The reason for the color scheme of the veil was symbolic. In Jewish tradition, blue represented the heavens, while red or crimson represented the earth. Purple, a combination of the two colors, represents a meeting of the heavens and the earth. Thus, purple can also be a representation of the Messiah in Jewish and Christian traditions. The only way into the Holy of Holies (God’s presence) was through the purple veil (Jesus Christ, the Messiah). Regardless, these colors were given by the inspiration of God, and all of God’s instructions had to be faithfully obeyed (compare 1 Chronicles 28:10–12).

As we will see, that veil of the temple was torn in two from top to bottom when Jesus died on the cross (compare Mark 15:38). According to the Jewish historian Josephus, that veil was four inches thick and was renewed every year. Horses tied to each side could not pull it apart. It barred all but the high priest from the presence of God—and even he could only enter it once a year—on the annual Holy Day of the Day of Atonement.

The Holy Place (compare 1 Kings 8:8–10) was also called the “greater house” or the “larger room” (2 Chronicles 3:5). It was of the same width and height as the Holy of Holies, but twice as long; thus the name “larger room.” Its walls were lined with cedar, on which were carved figures of cherubim, palm trees, and open flowers, which were overlaid with gold. Chains of gold marked it off from the Holy of Holies.

The porch, “vestibule” or entrance before the temple on the east was traditionally called the Ulam (1 Kings 6:3; 2 Chronicles 3:4). The length corresponded to the width of the temple (1 Kings 6:3). References to “Solomon’s porch” can be found in John 10:23; Acts 3:11; and Acts 5:12 (Authorized Version).

In the porch stood the two pillars Jachin and Boaz (1 Kings 7:21). These names, as the pillars themselves, were symbolic. The pillars did not support any part of the building. The names indicated strength and stability. Jachin means, “He shall establish,” and Boaz means, “in it is strength.” The names possibly conveyed the thought that God will establish in strength the temple and the true religion.

Chambers were built about the temple on the southern, western, and northern sides (1 Kings 6:5–6, 10). These formed a part of the building and were used for storage of the utensils of the tabernacle. They were probably one story high at first; two more may have been added later.

The inner court of the priests (2 Chronicles 4:9), called the “inner court” (1 Kings 6:36), was separated from the space beyond by a wall of three rows of hewn stone and a row of cedar beams (1 Kings 6:36). The tabernacle in the wilderness did not have such an inner court for the priests. The temple’s inner court of the priests contained the brazen Sea or the “Sea of cast bronze” (2 Chronicles 4:2–5, 10), and ten lavers of bronze (1 Kings 7:38, 39), corresponding to the bronze laver or basin of the tabernacle.

The brazen Sea stood on twelve oxen (1 Kings 7:25). Its purpose was to afford opportunity for the purification of the priests by immersion of the body. The ten lavers of bronze, each of which contained “forty baths” (1 Kings 7:38), rested on portable holders made of bronze, provided with wheels, and ornamented with figures of lions, cherubim, and palm trees.

In the tabernacle was no brazen Sea; rather, one bronze laver served the double purpose of washing the hands and feet of the priests as well as the parts of the sacrifices. But in the temple there were separate vessels provided for these tasks related to washings and the bringing of sacrifices. The brazen Sea held from 16 thousand to 20 thousand gallons of water.

According to 1 Kings 7:48–49, there stood in the Holy Place, before the Holy of Holies, the golden altar of incense and the table for showbread. This table was of gold, as were also five lampstands on each side of it, corresponding to the one golden lampstand of the tabernacle.

2 Chronicles 4:8 reveals that Solomon actually made ten golden tables of showbread and placed all of them in the Holy Place. But in spite of his initial dedication to God and His temple, he did not stay loyal and faithful to God, but allowed evil influences to persuade him to depart from Him.

The great court or outer court surrounded the whole temple (2 Chronicles 4:9), and corresponded to the courtyard of the tabernacle. Here the people assembled to worship God (Jeremiah 19:14; 26:2).

After the temple was built, Solomon dedicated it to the LORD by offering sacrifices in the courtyard or inner court of the priests. 1 Kings 8:63–64 reads: “And Solomon offered a sacrifice of peace offerings… On the same day the king consecrated the middle of the court that was in front of the house of the LORD; for there he offered burnt offerings, grain offerings, and the fat of the peace offerings, because the bronze altar that was before the LORD was too small to receive the burnt offerings, the grain offerings, and the fat of the peace offerings.”

The altar of burnt offerings was inadequate for the vast number of sacrifices given on this occasion. Therefore, Solomon set apart the middle of the court of the priests to bring sacrifices, apparently on an additional altar (compare 2 Kings 16:14).

We see, then, that the temple took over the function of the tabernacle.

The Millennial Temple

And so will the new temple at the time of the Millennium, which is described in the book of Ezekiel, beginning with the 40th chapter. Specifically mentioned are: a wall around the entire temple; eastern, northern and southern gateways; gate chambers; a vestibule of the gateway; an outer court with chambers; an inner court; tables on which to slay the offerings; an altar made of wood; chambers for the singers; a Sanctuary or Holy Place; and the Most Holy Place.

A Tour of the Original Tabernacle

Returning to the original tabernacle in the wilderness, we will begin our tour of the complex of the entire tabernacle, by commenting briefly on the concept of the tabernacle and its furnishings.

We read in Exodus 26:1: “Moreover you shall make the tabernacle with ten curtains…”

The tabernacle was actually a portable temple. The word “tabernacle” comes from the Latin, tabernaculum, meaning tent. The Hebrew word means “to settle down, to abide, to dwell, to live in a tent.” It describes a “dwelling place.” Sometimes it only refers to the tent. In other places, it means the tent with the surrounding courtyard.

In Exodus 26:6, we read: “… so it may be ONE tabernacle…” There was only to be one tabernacle, one altar, and one place of worship. God’s instructions were that Israel was to have only one place of sacrifice, and that this one place was in front of the tabernacle (compare Leviticus 17:1–5).

The high quality of the precious materials making up the tabernacle shows God’s greatness. The portable nature of the tabernacle shows God’s desire to be with His people as they traveled.

Symbolism

The tabernacle prefigured Jesus Christ and His ultimate sacrifice, who “tabernacled” or “dwelt” among men (compare John 1:14: “And the Word became flesh, and dwelt among us…”).

God’s glory entered Herod’s temple in the person of Jesus Christ, who “tabernacled” among men. After Christ’s death, God’s glory departed from the temple, and it was destroyed. But His glory lives today in His Church.

This means that the tabernacle symbolizes Christ AND His Church.

The Church is a habitation of God—a dwelling place—through His Spirit (compare Ephesians 2:19–22). This includes each individual believer (compare 1 Corinthians 6:19). We might say, the Christian is a spiritual tabernacle. And so is the Church of God (compare Psalm 15:1).

The tabernacle had TEN curtains—not just one curtain (compare Exodus 26:1). This might represent the fact that at times, there may be in existence several Church organizations, and even several Church eras, but they are all ONE in that they all belong to the ONE true Church wherein the Holy Spirit dwells (Romans 8:8–9; Ephesians 4:4–6; 1 Corinthians 12:11–14). The ten curtains had to be of “fine woven linen” (Exodus 26:1), which is symbolic of the righteousness of the saints (Revelation 19:8). God JUDGES all of us individually, and He judges His Church—“ten” is the number of judgment. That is why God gave us His Ten Commandments, on the basis of which we will be judged.

The curtains were to be embroidered with cherubim—angelic beings—to confirm that the angels of God closely watch over or, in that sense, “pitch their tents” round about the Church.

The description of the tabernacle in Exodus 25 begins with the inside, according to God’s view, and moves to the outside. God begins from Himself, working outward toward man. Salvation is from the LORD. God must grant us salvation—we cannot get it through our own efforts, apart from God.

It also shows a movement from the more valuable to the less valuable products or material used—notice that God’s instructions has one move from the Most Holy Place to the Holy Place and finally to the outer area, as we will now do.

The Holy of Holies

We begin our tour of the tabernacle in the Holy of Holies, inside the tent:

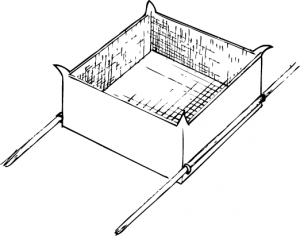

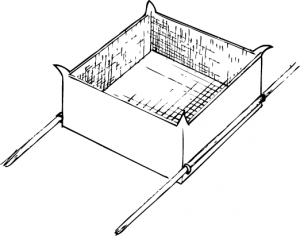

The Ark of the Covenant

We are first introduced, in Exodus 25:10, to the Ark of the Covenant or of the Testimony.

It was made of acacia wood. It was durable and resistant to disease and insects, making it the most suitable material for constructing the ark (Exodus 25:12–14). Rings of gold allowed the ark to be carried on poles. It was not to be picked up by hand or carted about (Exodus 25:16). Inside the ark or chest were the two tablets of the Ten Commandments, as well as Aaron’s rod. Then there was a special container in which were the manna, holy anointing oil and other objects of special meaning.

It was made of acacia wood. It was durable and resistant to disease and insects, making it the most suitable material for constructing the ark (Exodus 25:12–14). Rings of gold allowed the ark to be carried on poles. It was not to be picked up by hand or carted about (Exodus 25:16). Inside the ark or chest were the two tablets of the Ten Commandments, as well as Aaron’s rod. Then there was a special container in which were the manna, holy anointing oil and other objects of special meaning.

There are five names given to the ark in the Old Testament:

The ark of the covenant, because it contained the two tablets of the law (Numbers 10:33).

The ark of the testimony (Exodus 25:22), because God testified about Christ’s holiness and man’s sinfulness.

The ark of God [or of the LORD], because it was the only visible throne of God (1 Samuel 3:1–4; 2 Samuel 6:9).

The ark of Your [God’s] strength, because of God’s miracles associated with the ark (Psalm 132:8).

The holy ark, because it was on top of the ark where God dwelt, between the two cherubim, and from where He spoke to Moses (2 Chronicles 35:3).

Symbolism

The ark of the covenant and its material—acacia wood and gold—are a type of the humanity and deity of Christ.

Since the tabernacle also represents the Christian in whom Christ lives, it shows that we, even though we are human, must be purified and become more and more as God is. Our faith, for instance, must be found more precious than gold.

Finally, Aaron’s rod is a symbol of the resurrection; that is, of the resurrection of Jesus Christ, as well as our future resurrection.

The Mercy Seat

Continuing in Exodus 25:17–18, we see a description of the “Mercy Seat”:

“You shall make a mercy seat of pure gold… And you shall make two cherubim of gold… at the two ends of the mercy seat.”

The term “mercy seat” is an English translation of a Hebrew noun, which means, “the place of propitiation.” It is derived from a verb, meaning, “to atone for,” “to cover over” or “to make propitiation.” The mercy seat was the lid for the ark of the covenant—that is, it was placed upon the ark—as well as the base on which the cherubim were to be placed. The ark, then, was the place where the mercy seat rested. It was the place where sins were covered—hence, the name “the place of propitiation.”

Exodus 25:20 continues: “And the cherubim shall stretch out their wings above, covering the mercy seat with their wings, and they shall face one another; the faces of the cherubim shall be toward the mercy seat.”

The mercy seat was overshadowed by two golden cherubim. These angelic beings were to protect the mercy seat, the ark and its contents; their outstretched wings were to provide a throne for God. Their faces were to be toward the mercy seat, bowed in adoration and humility before God.

Symbolism

The mercy seat was made of pure gold, which represents God’s throne, from which He reigns, and from which He forgives (Psalm 99:1–5, 8).

It also shows our potential—to rule as kings and priests with, and under Christ, ON THIS EARTH.

The Sanctuary

In our tour, we leave the Holy of Holies, pass through the inner veil, and enter the Sanctuary:

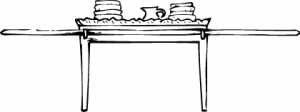

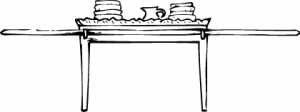

Table for the Showbread

The first furnishing that God describes within the Sanctuary is the Table for the Showbread. Exodus 25:23, 30 reads: “You shall also make a table of acacia wood… And you shall set the showbread on the table before Me always.”

The table was used to display twelve loaves of unleavened bread, in two rows with six loaves in each row (compare Leviticus 24:5–6). The loaves were changed every Sabbath and, having been consecrated, were eaten by the priests in the Sanctuary (Leviticus 24:9). The bread had to be there “always” (Exodus 25:30). It was known as holy bread (1 Samuel 21:4).

Frankincense was placed on each row of bread, “that it may be on the bread for a memorial, an offering made by fire to the LORD” (Leviticus 24:7).

Frankincense was placed on each row of bread, “that it may be on the bread for a memorial, an offering made by fire to the LORD” (Leviticus 24:7).

Also, there were cups associated with the table for the showbread, probably containing wine and oil (Exodus 25:29).

The table was to have rings and poles so that it could be transported properly (Exodus 25:26–27). The poles protected the holy object from being touched by human hands.

Symbolism

The showbread is a type of Christ—the Bread of God—who nourishes the Christian. It shows that God gives us physical AND spiritual food (John 6:11, 26–27, 33).

The twelve loaves represent the twelve tribes of Israel. As the Church of God is spiritual Israel today, the loaves represent our fellowship with God. They also symbolize our gratitude to God for our daily bread, without worries and doubts (compare Luke 11:3; Matthew 6:25–26, 33–34).

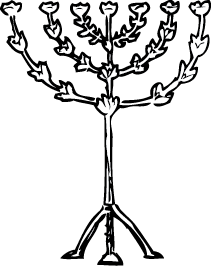

The Golden Lampstand

Next, we are introduced to the golden lampstand (“menorah”) inside the Sanctuary. Exodus 25:31 states: “You shall also make a lampstand of pure gold…”

As verses 31 and 32 explain, all of the elements of the lampstand were to be hammered out of one solid piece of gold. One of the seven lamps was to be placed in the center, flanked by three branches on either side. Seven represents completion. It burned continually, and the priests had to tend it from evening until morning, but not during the day (compare Exodus 27:20–21).

As verses 31 and 32 explain, all of the elements of the lampstand were to be hammered out of one solid piece of gold. One of the seven lamps was to be placed in the center, flanked by three branches on either side. Seven represents completion. It burned continually, and the priests had to tend it from evening until morning, but not during the day (compare Exodus 27:20–21).

Symbolism

The lampstand provided light for the ministering priests and typified Christ, the Light of the world (compare John 1:5; 8:12). Natural light was excluded from the tabernacle, as the natural mind does not receive the things of God. Christ enlightens us (compare Ephesians 1:15–18). He must give us His light of understanding (compare Ephesians 5:8–14).

The lampstand is also symbolic for the Church and, to an extent, its seven Church eras, which are referred to in Revelation 1:20 and described as seven “lampstands” or “candlesticks.” But there is an important difference between the ONE lampstand with seven arms, and the SEVEN different candlesticks of the Church in the book of Revelation—one, two or three of those candlesticks could be removed (compare Revelation 2:5), while others would still remain.

The lampstand of the tabernacle is also symbolic for the single Church member (compare Matthew 5:14–16). It signifies his light-bearing and witness through worship and right conduct (compare Philippians 2:14–15)

The Oil for the Lampstand

Exodus 27:20 continues to describe the oil for the lampstand, as follows:

“And you shall command the children of Israel that they bring you pure oil of pressed olives for the light, to cause the lamp to burn continually.”

The oil was obtained from olives that were beaten rather than crushed. It gave finer quality, burned more brightly and with less smoke.

It was so holy that—according to Jewish tradition and understanding—the people were strictly forbidden to copy it for personal use.

Symbolism

The oil symbolizes God’s Holy Spirit, which is unique. It cannot be copied. Either one has God’s Holy Spirit, or one does not have it (compare Matthew 25:1–4; Zechariah 4:2–6). It had to be renewed daily, in the morning and in the evening, based on Leviticus 24:3–4. Likewise, Christians must continually “stir up” God’s Holy Spirit—that is, they must make use of this power in their lives constantly (compare 2 Timothy 1:6).

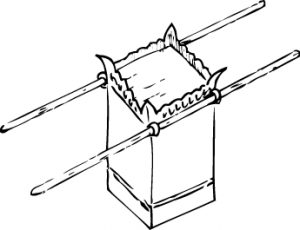

The Altar of Incense

Another important feature within the Sanctuary, the altar of incense, is mentioned later, in Exodus 30:1: “You shall make an altar to burn incense on; you shall make it of acacia wood…”

Logically, this section concerning the altar of incense, should follow the description of the making of the table for the showbread and the golden lampstand, as they were all articles in use in the inner part of the Sanctuary.

The reason why the description of the altar of incense comes out of order here may be connected with the fact that it follows the section concerning the inauguration of Aaron and his sons as priests (compare Exodus 28:1–43; 29:1–46). The burning of incense is now listed first among their priestly functions. And they are commanded not to offer “strange incense” (Exodus 30:9). But that is exactly what Aaron’s sons, Nadab and Abihu, did on the day of their inauguration (compare Leviticus 10:1–4). The order of commands concerning the incense altar here sets the stage for those coming events. And it establishes the extreme importance of precise obedience to the ritual commandments, especially by the priests.

The reason why the description of the altar of incense comes out of order here may be connected with the fact that it follows the section concerning the inauguration of Aaron and his sons as priests (compare Exodus 28:1–43; 29:1–46). The burning of incense is now listed first among their priestly functions. And they are commanded not to offer “strange incense” (Exodus 30:9). But that is exactly what Aaron’s sons, Nadab and Abihu, did on the day of their inauguration (compare Leviticus 10:1–4). The order of commands concerning the incense altar here sets the stage for those coming events. And it establishes the extreme importance of precise obedience to the ritual commandments, especially by the priests.

The altar of incense stood before the curtain or veil that shut off the Holy of Holies (Exodus 30:6). Sweet-smelling incense was burned on it morning and evening when the priest tended the lamp (Exodus 30:7–8). It was so holy—as was the anointing oil—that the people were strictly forbidden to copy it for personal use.

It was made of acacia wood (as was the ark of the covenant and the table of the showbread). Rings and poles were used to carry the altar, signalizing the great respect that was demanded for the transportation of these holy furnishings.

Symbolism

Incense symbolizes our prayers (compare Revelation 5:8; Psalm141:2). We can have constant access to the Holy of Holies and the Sanctuary through our prayers (compare Hebrews 10:19, 22).

Aaron sacrificed twice a day. This symbolizes the need for our perpetual prayers (compare Revelation 8:3–5).

In addition, the altar of incense and its associated functions, including the ministering priest who burned incense on the altar of incense, symbolize Christ, our Intercessor (compare Hebrews 7:25).

The incense itself also represents Christ Himself, who prays on our behalf. We are praying to God the Father through Jesus Christ and in His name—that is, Christ Himself intervenes on our behalf before God the Father, explaining and communicating to the Father what we might have wanted to say, but could not or did not. Christ, the Lord (1 Chronicles 28:9), searches our hearts and understands all the intent of the thoughts. We read that we don’t know what we should pray for as we ought, but that Christ, the life-giving Spirit, makes intercession for us with groanings which cannot be uttered (compare Romans 8:26–27, 34; 2 Corinthians 3:17; 1 Corinthians15:45).

The Inner Veil

As we mentioned, when Aaron the priest went from the Holy of Holies to the Sanctuary or Holy Place, or vice versa, he had to pass through the “inner veil,” separating the Sanctuary from the Holy of Holies.

Exodus 26:33 says about the veil:

“And you shall hang the veil from the clasps. Then you shall bring the ark of the Testimony in there, behind the veil. The veil shall be a divider for you between the holy place and the Most Holy.”

The inner veil separated the Holy Place (which contained the altar of incense; the golden lampstand; and the table for the showbread) from the Holy of Holies (which, as we will recall, contained the ark of the covenant and the mercy seat; compare Exodus 26:34–35).

The inner veil was to hang from four pillars of acacia wood overlaid with gold (compare Exodus 26:32).

The priest entered the Holy Place each day to tend to the altar of incense, the golden lampstand, and the table for the showbread. But only the high priest (apart from Moses) could enter the Most Holy Place—and that only once a year, on the Day of Atonement (“the day of covering over”)—to make atonement for the sins of the nation as a whole (compare chapter 3 of this booklet).

Symbolism

The priests made the journey on behalf of the people, and therefore symbolized and represented the Church. Each Israelite felt the presence of God. The way of Israel was the way of the symbol—by entering the court, moving from the altar of burnt offering and the laver through the outer veil into the Sanctuary with its bread, lamp and incense, and then moving through the inner veil into the Most Holy Place with the law, mercy and atonement, to the ultimate presence with God.

The inner veil represents Jesus Christ. The Israelites had to cover the entire tabernacle when they transported it, as they did not have any access to God’s Holy Spirit. When Jesus died, the curtain in the temple, which had replaced the veil of the tabernacle—but which had maintained the same function and symbolism—tore from top to bottom (compare Mark 15:37–38). This figuratively pointed at our free access to God.

The inner veil is a type of Christ’s body, granting us access to God, the Holy of Holies, and God’s Holy Spirit, as this is clearly revealed in Hebrews 10:19–20: “Therefore, brethren, having boldness to enter the Holiest by the blood of Jesus, by a new and living way which He consecrated for us, through the veil, that is, His flesh.”

Outside the Tent

In our tour, we now move from the Holy Place or Sanctuary to the area outside the tent. In doing so, we will adopt the reverse order from our own journey, and view as it would appear for the Israelite entering the tabernacle complex area:

The Court

Exodus 27:9 tells us that the Israelite would first enter the court: “You shall also make the court of the tabernacle. For the south side there shall be hangings for the court made of fine woven linen…”

Before the tabernacle or tent, there was to be a court or yard, enclosed with hangings of the finest linen that was used for tents.

Symbolism

This court was a type of the Church, enclosed and distinguished from the rest of the world. Exodus 27:10 explains that the court was supported by pillars, denoting the stability of the Church, hung with clean linen (compare again verse 9), which describes the righteousness of the saints (Revelation 19:8).

These were the courts David longed for and coveted to reside in (Psalm 84:1–2, 10), and into which the people of God were to enter with praise and thanksgiving (Psalm 100:4).

Yet, this court would contain but a few worshippers. The same is true for God’s Church today. God must call us into His Church. Nobody can come to Christ unless the Father draws him or her.

Exodus 27:17 says that “All the pillars around the court shall have hooks or bands of silver…” This shows that the court and its pillars also symbolize Jesus Christ. Psalm12:6 says that “The words of the LORD are pure words, Like silver tried in a furnace of earth, Purified seven times.” In God’s court or Church, we must uphold the words of God, which are pure words, like silver, which is tried and purified to completeness.

The Gate of the Court

The gate of the court (compare Exodus 27:16) points at Christ, through whom we have access to His Church (compare John 10:1, 7, 9). He is also our access to God the Father (John 6:44, 65).

We NEED the Church of God—we have to be IN the “court.” We cannot remain outside, or leave the court (compare Ephesians 4:11–16). Conversely, people who are outside the court are those who are not “in” the Church and who do not want to hear God’s truth.

But just being “in” the Church by attending Church services on and off is not enough. Rather, we must GROW in the knowledge of Jesus Christ and we must be following His lead. Notice the warning in Revelation 11:1–2, which seems to be addressing a literal temple still to be built in Jerusalem prior to Christ’s return, and, in a figurative way, those Church members who are not content to move from just being “in” the Church to a more perfect understanding of God’s truth.

The Altar of Burnt Offering

Once an Israelite had stepped into the court, he would first see the altar of burnt offering, as described in Exodus 27:1–2: “You shall make an altar of acacia wood… And you shall overlay it with bronze…”

The altar was made of wood covered with bronze in order to make it lightweight for transport and still fireproof. All the sacrifices within the sacrificial offering system were made on this altar.

The altar was made of wood covered with bronze in order to make it lightweight for transport and still fireproof. All the sacrifices within the sacrificial offering system were made on this altar.

It was the first thing that the people saw as they entered the tabernacle courtyard. The altar signified that all who entered were defiled by sin and could approach God only by way of sacrifice. The fire on the altar was never to go out (compare Leviticus 6:9, 13).

Symbolism

The brazen altar of burnt offering pictured Jesus Christ. That the fire on the altar never went out, shows that Christ’s supreme Sacrifice, which was given once and for all, still has permanent application, relevance and importance for us today, AND it will have that same importance for all eternity. Christ is still referred to as the LAMB throughout the book of Revelation, even after He has returned, and after the New Jerusalem has descended from heaven.

The brazen altar of burnt offering stood on a hill, which is symbolic for Christ, who died on the hill of Golgotha. Christ sanctified Himself for His Church, as their altar (John 17:19). Hebrews 13:10 tells us: “We have an altar from which those who serve the tabernacle have no right to eat.” But today, Christ’s true disciples are allowed to eat from that altar—Jesus Christ.

The High Priest went on the Day of Atonement with a golden censer into the Holy of Holies, bringing incense and burning coals of fire from that altar (compare Leviticus 16:12–13; Hebrews 9:2–4).

Revelation 8:3 mentions a golden censer in heaven; and Ezekiel 28:14–16 mentions burning coals of fire or “fiery stones” in heaven as well (Please note that the quoted passage in Ezekiel 28 describes Lucifer’s fall from “the mountain of God” in heaven.) As the “earthly” burning coals of fire were taken from the altar of burnt offering, they symbolize the sufferings of Christ. The burnt offering symbolizes Jesus Christ, and He had to go through fiery trials of suffering.